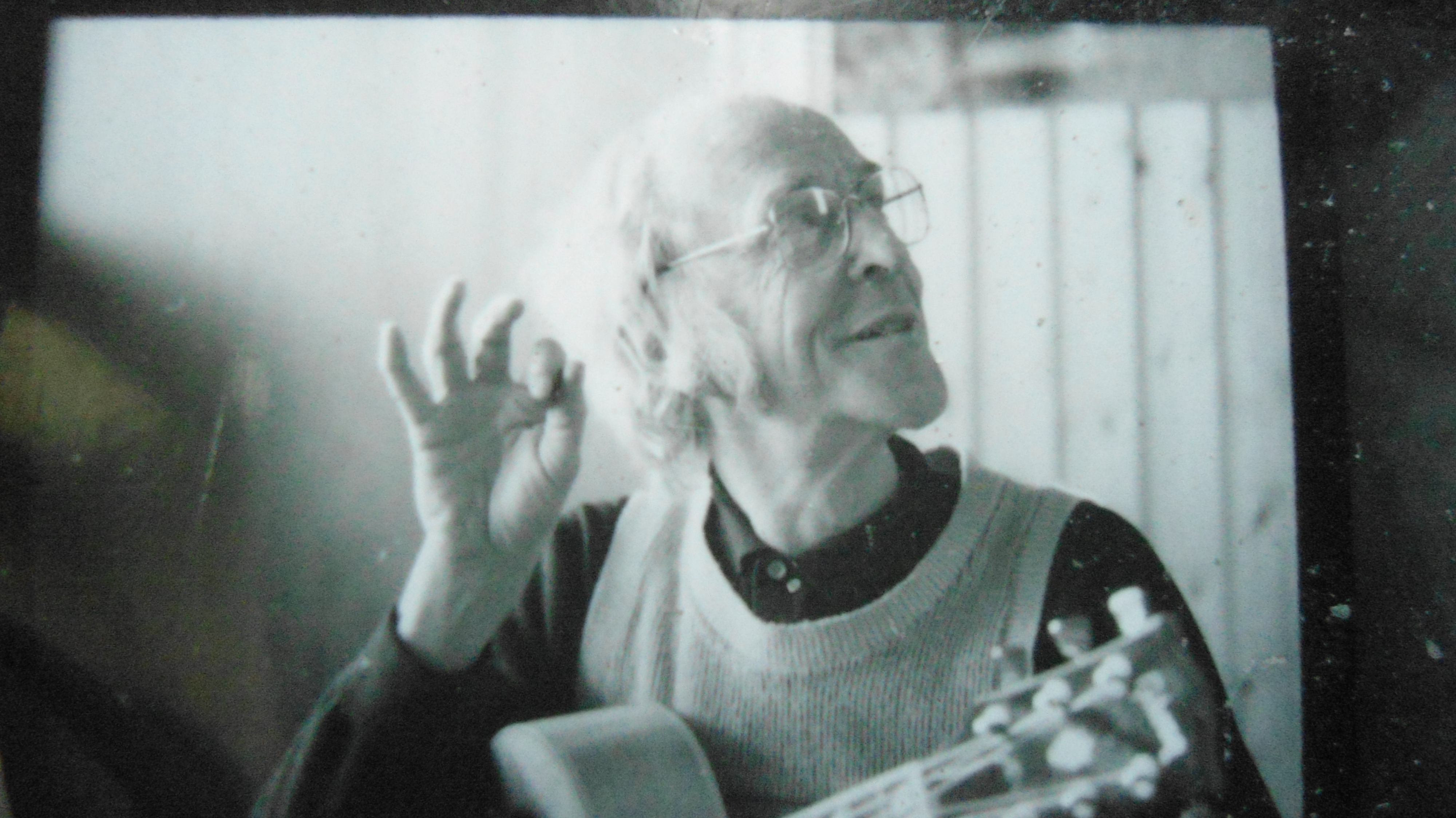

Growing up the son of a musician is a unique experience. But growing up the son of a universally accepted genius in jazz is life defining. Despite his critical reputation, Jimmy Raney’s manner was matter of fact, almost like a librarian in his quiet, understated yet informative and economic manner. Watching him play was marvelous because he was so nonchalant about it. Something about the act of performing a great feat without seemingly trying seems to carry universal appeal. Right leg casually crossed over left, his left hand gripped the guitar purposefully angled for just the right creative leverage. He often kept a cigarette stuck smoking in the strings on the headstock, awaiting a drag between choruses. There was also his trademark double-jointed right thumb, sticking up like a small winter hat, picking his quicker-than-the eye Morse code precisely and delicately with the steadiness of a surgeon’s hand. I am certain I have heard that a number of studious plectrists actually went home bending back their thumbs in the hopes of improving their picking technique.

As he continued for another chorus, he would heave his chest just a bit to take a breath; you think there is a certain discomfort there but then you realize he’s coming up for air before pulling you in for a another ride in variation and development. There was a delicate balance between his familiar yet engaging signature phrases and that extra something that differentiated that solo from a prior rendition, a beauty that thrived on a delicate tension between the expected and the new. There was also the element of risk perhaps: he might not play something quite up to the height of the bar he had raised prior. But that never happened. He just didn’t have it in him to let you down musically. For us Raney children, it was, “Of course, why would anybody play any other way?” Not realizing (at least at the time) how incredibly difficult and rare to do something “that right” was.

There was absolutely unique grace in his technique. It wasn’t perfect in the Segovia sense. He used his pinky sparingly at the tops of phrases. But there was none of the wasted motion, gyrations or head rocking in reverie typical of many guitarists.He could get up from point A to point Z on the neck in a heartbeat and there was never any stress or strain in the way he went about it. He modeled his sure-handed technique not really from guitar players but rather his teachers and fellow masters like Charlie Parker, Stan Getz and Al Haig who wasted no motion in the reproduction of notes. Also there was tremendous drive in those delicate fingers. Deceptively so, since many guitarists would probably be shocked at the height of his guitar action based on his delicate sound and might find themselves cutting a new callus on his instrument. His preference for this action was because he felt more in control of the notes: the more forcefully he had to grip them, the more they were his.

When the set was over, he wanted to talk about other things besides music or perhaps not talk at all. He was a bit shy with new people. He disliked phoniness and mindless chitchat, unless of course he was the one doing it. And then of course there was the endless stream of requests for lessons and the likewise ceaseless preamble that accompanied such requests. These solicitations were often disingenuous whims and wastes of his time. He could also grow weary at times of the over-eager audience members with stories of common acquaintances or experiences that marginally tied them to him. He did enjoy compliments, but he almost backed away from them. To enjoy them would almost seem like a public display of self-indulgence.

The audience members he did like however were the humorous types, especially those that diverted the subject from the obvious musical topic at hand. I never heard him laugh louder than when guitarist Howie Collins would spin one of his sardonic stories. But you didn’t have to be a player to get in his good graces; you just needed a sense of humor, a good idea where to open up the lines of conversation and also sensitivity to when he was not in the mood.

And there weren’t just any audience members showing up to his gigs. Major players could be found coming down to hear the Raney magic. Among them Art Blakey, John Abercrombie, Kenny Burrell, George Benson (who sat in), Tal Farlow, Tommy Flanagan and Charlie Mingus and many others. His playing during the 70s and 80s was just astounding and if you didn’t come down to catch him live you were truly missing something; gigs at Bradley’s were an event and everybody knew about it. But by the late 70s and 80s he began to suffer more and more from an intermittent hearing disorder of the inner ear, Miniere’s disease. He was already nearly deaf in one ear for quite some time. But because he was so brilliant and his timing was so razor sharp, he was able to actually play from his head and follow the tempo by watching the count in and foot tapping from the players. Amazingly even musicians on the bandstand and off couldn’t tell he wasn’t hearing what he was playing.

Coupled with the unpredictable disease, he developed a rather retiring life-style. In some ways he was growing tired of playing a lot and preferred the seclusion of Louisville. To entertain himself, comedy, astrophysics and his cats would occupy much of his time. He subscribed to Scientific American for years and had 6-7 cats having the run of the house. The TV programs he enjoyed for the most part were comedies, and he watched them religiously, like Mash, All In The Family and especially Barney Miller, which he probably videotaped every episode. But even his TV watching was a creative outlet, for example commercials. One hilarious trick he would do would be recite verbatim in mock seriousness a line of dialogue from an “informative”commercial just a few seconds before the actual delivery of the dialogue. I still chuckle thinking about a Lorne Greene commercial for life insurance, where my father would intone Greene’s deep voice the line, “Who pays? You do!” three seconds before Lorne delivered it. A kind of “comic reverb” effect if you will. He was of course always being creative and musical.